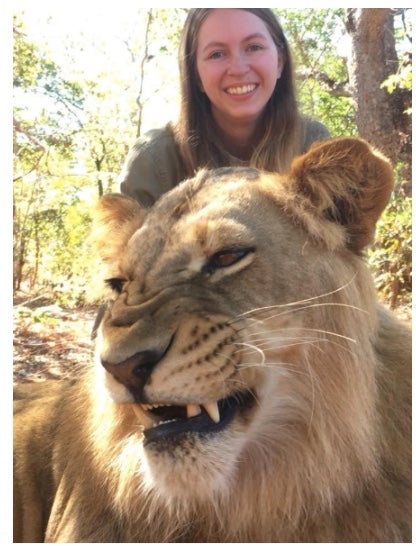

2018 Travel Grant Winner Peri Beckerman on her Experience in Zambia

For “Language Shift on the Bakota Plateau”

Peri traveled to work on language documentation at Georgetown’s field school in Zambia.

I am incredibly grateful to the Global Medieval Studies Program for making it possible for me to go to Zambia and learn more about the Medieval Period there. As the Zambian Medieval Period looks so vastly different from what many people usually think about when they hear “medieval” (Europe with castles, many churches, knights, and the like), it is difficult to conceptualize how the same label classifies Zambian history as well.

I participated in a few different areas of historical research through archeology and linguistics, excavating a trench and surveying the local area, as well as conducting interviews in Ila, with the use of an interpreter. These were our methods of data collection for the Zambian Medieval Period.

The Zambian Medieval Period was filled with trading within the region but also extended as far away as India. During excavation, we found some cowrie shells, which belong to mollusks only found in the Indian Ocean. This trading was occurring between the years around 900-1200 CE. This discovery could come as a surprise to some people, as it can be hard to think about people trading who was not your ancestors, or if there was not a written record to draw upon for another type of proof. While many in Europe were writing documents on major events, archeologists and linguists studying the medieval period of sub-Saharan Africa often have to rely on educated guesses on the day-to-day of the people living in that era, which is heavily based on cataloging the changes in material culture or word usages.

When we saw the changes from glass beads from India to ostrich egg beads, we guessed that either trade with India was just beginning or had not started yet. When we collected words through the interview process that appear to be related or borrowed from another language (Zambian or not), we can guess that trade or conflicts were occurring between two or more different cultures.

One thing that was very important to my understanding the medieval period in Zambia was discovering that several layers of our excavated trench had a mixture of stone tools and iron tools. Usually, when people think of the Middle Ages, they think of ironworking and a lack of stone tools. The great and distinct overlap we found of stone and iron tools showed us that there is no strict divide between the two ages. As many people now say, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” and that was certainly a phrase that could be attributed to the Zambian Medieval Period. There is no one “right way” to have a Medieval Period, and to completely eliminating the use of stone tools might not have been the right move in terms of innovation. The Zambians knew what was best to use in their environment, so calling them certain names like “savages” or “primitive” during this time period would not have been correct. This experience helped reinforce this message and lesson in my mind, and was necessary in acknowledging that the concept of history is different for every culture.

Image credit: Peri Beckerman